Wine critic Bordeaux

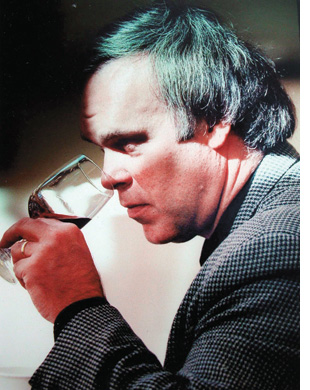

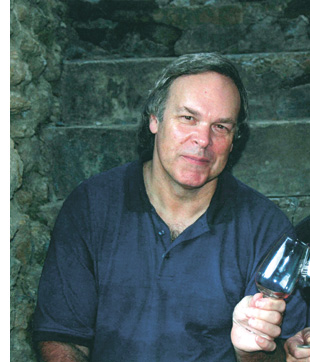

Robert Parker: Bordeaux’s Point Man Robert Parker owes his wife, big time. If she hadn’t been quite so fetching—and he so afraid of losing her—he may never have traveled to France to see her during her junior year abroad. He may never have tasted French wine, and his oenological experiences may never have gone beyond that one bottle of Cold Duck that made him sick. Years later, were it not for her threats to divorce him over t-he small fortune he was spending on wine,

Robert Parker owes his wife, big time. If she hadn’t been quite so fetching—and he so afraid of losing her—he may never have traveled to France to see her during her junior year abroad. He may never have tasted French wine, and his oenological experiences may never have gone beyond that one bottle of Cold Duck that made him sick. Years later, were it not for her threats to divorce him over t-he small fortune he was spending on wine,But he did, and the result was « The Wine Advocate », which Parker—then a practicing lawyer-launched in 1978. Still sold by subscription and devoid of advertising, the now famous newsletter was strongly influenced by one of the activists of that period: Ralph Nader. “At the time, there were some terrific writers and wonderful books about

the history of wine, but there was nothing that was pro-consumer,” he explains. “I wondered why no one was simply tasting wines and giving a candid opinion of what they thought of them.” So Parker decided to do just that, accompanying his comments with scores based on the 100-point scale familiar to every American student.

The ethical approach he brought to this endeavor was shaped by a law school class taught by Sam Dash, who later became chief counsel to the Senate Watergate Committee. “It was all about conflict of interest” recalls Parker. “So when I realized that even the best wine books of the era were written by people involved in the wine trade in one way or another, I knew they couldn’t really be critical of sacred estates.” He therefore resolved to remain independent, purchasing his own wines, never soliciting samples and paying for his own trips and lodging. While acknowledging that many unsolicited samples make their way to his office in Monkton, Maryland, Parker also says that he typically spends some $100,000 on wine annually. In addition to « The Wine Advocate », Parker has published 11 books on wine, including the renowned « Bordeaux », whose 2003 edition received the new subtitle, « A Guide to the Best Wines in the World ».

His writings have been translated into numerous languages, and his work has earned him international fame, honors and awards including the prestigious Legion of Honor presented by President Chirac himself. Not surprisingly, Parker has also received a good dose of the criticism that inevitably accompanies such influence. « FRANCE » Magazine recently talked with him about his detractors as well as his extraordinary talent and the striking evolution in the winegrowing region that remains dearest to his heart: Bordeaux.I don’t know that there’s any one answer except to say that I’m passionate about what I do. I absolutely love it and have from the beginning. Actually, it took me a while to realize that I was better at tasting than most people, and even then

I thought it was simply because I was more single-minded and immersed myself in the field more than anyone else.

But I think tasting is really a question of concentration and focus. It’s not something that I bring to other areas of my life-my general practitioner jokingly says I’m a sort of idiot savant. And maybe there’s a little truth to that. I don’t have a photographic memory for anything else, and when I was practicing law, I couldn’t absorb a lot of the research.

I just had no interest in it.

That’s a distressing thought! Luckily, when it comes to wine, I do have this extraordinary photographic recall of smells and textures. I always remember where I had it, whom I was with. And I’ve always had that ability. Even in a noisy crowded room, when there’s a glass of wine under my nose, it’s like the entire energy and faculties of my brain become compressed into a little zone that smells, tastes, analyzes and breaks down the wine. I just love doing that and never get tired of it. What’s great about wine is that with each new vintage, you basically go back to school, you’re forever a student.

And you know there will be exciting new wines and depressing disappointments. So there’s always the thrill of the chase.

When I’m on tasting trips, I don’t go out at night and haven’t for the past 15 years. When I was in my thirties, I could burn the candle at both ends, but these days, I start around 8 A.M., work until 6 or 7 P.M., then go back to the Novotel or Sofitel and have a salad and some water, do some reading and go to bed. So I’m fresh and don’t have the fatigue factor to worry about. I have also learned through experience to avoid certain foods, since they provoke undesirable reactions on your palate.

Well, I’m not much for sweets, but chocolate is a real no-no.

It leaves a bitterness that throws off textures and flavors. Watercress also imparts an incredible bitterness, and I avoid all spicy foods on tasting trips. I don’t think I’m as influential as some people say, but I’m not naïve either, and I feel that

I have a responsibility to be fair, to bring to the tasting table-not only at 8:30 in the morning but at 6:30 at night-every bit of my ability to judge someone’s wine fairly.

I tell people all the time, “If you think Parker sits at home every night drinking 99-point wines, you’re wrong.” I drink a lot of wines from the Côtes du Rhône, the Loire Valley, Alsace.... My cellar is 90 to 95 percent French. My tastes are certainly diverse enough to recognize that there are some great wines from South America, Australia, Italy, Spain and so on, but I’m a Francophile. France is where I learned about wine, it’s my point of reference, and regardless of what anyone might say, no one beats the French in making wines of extraordinary longevity and elegance that actually work with food. A lot of people try, but it’s really hard. The French have centuries of experience and very special regions where these wines are produced.

Every August I take off two weeks, and at the end of that period, I always ask myself, my God, how did I get through two weeks without good wine?

Bordeaux today is certainly a higher quality, more consistent wine, and there is now a greater diversity of wines produced in this region. When I started writing, only about 20 to 25 percent of the top 100 estates-those in the 1855 classification as well as St. Emilion and Pomerol, which are not part of that classification-were producing wines of high quality that were proportional to their reputation and pedigree. Today, I would say that number has increased to 90 or 95 percent. Plus you have a new generation of men and women who have been pushing quality and making names for estates that I had never even heard of 10, let alone 20 years ago.

It really started with Emile Peynaud, the famous professor who died recently. When he began working as a consultant, his leading advice was that you have to pick ripe fruit. In his book, The Taste of Wine, he says that to make great wine, you can’t rely only on terroir, you have to pick ripe fruit; otherwise you end up with green tannins, high acid and unripe flavors. Just like when you eat an apple or peach, you want grapes to be ripe. He was the first to get people to realize that quality has to come from the vineyard, that conservative viticultural techniques are important.

A number of new vinification techniques have also been introduced. Without getting too technical, what do you think of the changes that have taken place in Bordeaux cellars over the past two decades?

A number of new vinification techniques have also been introduced. Without getting too technical, what do you think of the changes that have taken place in Bordeaux cellars over the past two decades?First of all, I don’t like to use the word “elegant,” even though I think it’s a given that Bordeaux are wines of lightness and elegance even in the more powerful, concentrated vintages. Why? Because I railed against its use by the British press as a euphemism for wines that were diluted and insipid. In retrospect, that may have been a mistake, since I am often accused of liking over-extracted, heavy-duty, new oaky wines, and that’s a myth.

Yes, that was a watershed vintage for me. I thought it was great, but other prominent American wine writers didn’t agree and actually thought it was a grotesque vintage and described it in pejorative terms. I never thought that. I had only five years’ professional experience at the time, but I remember this extraordinary opulence and richness. So I looked at cellar masters’ notes and talked with the old timers in Bordeaux about the great classic vintages such as 1961 and 1959, 1947, 1929, 1921 and 1900, and all of them said that they thought all those wines had been too delicious when they were young, that they had too much fruit, that they were atypical, not classic. It was only after 10 or 15 years when the baby fat was gone that you saw their structure, that the great terroirs they came from emerged.

Already, Mouton Rothschild, Cheval Blanc, Haut Brion, Pétrus and others are becoming luxury items. Barring any major unforeseen developments in the world economy, I think that these wines will be increasingly seen as collectors’ items, which is rather sad. It’s the rule of supply and demand:

The production of all these famous wines is finite. It’s the same as it was 100 years ago, yet every year, the number of people around the world who come into the market with enough discretionary income to buy them increases significantly. Look at the Chinese - I think we’re going to see an extraordinary demand for fine wines from them. They like alcohol, they like the color red - it denotes good luck - and they are a tea culture that loves the structure, astringency and firmness of tannin. And I think that’s why they love Bordeaux. For Americans, weaned on sweet cola beverages, tannin is practically an alien component on the palate.

I see a caste system. Given the supply and demand situation I just described, the prices of wines from very famous estates that deliver high quality will keep rising. They will pull up other top Bordeaux estates - not all of them, but many of them. The same will happen in Burgundy, where there is limited production of top wines, and in the northern Rhône. Below that level - and this goes for the great wines of Italy and Spain as well - the proliferation of vineyards in other parts of the world will bring a leveling and perhaps even a decline in prices. You’ll see more branded wines and a lot of competition for consumer interest.

I think a lot of them have ambivalent feelings - most of them know me and probably have a great deal of respect for the way I work and think I’m a nice guy. But they also resent that anyone -whether they are French or foreign - has such influence or perceived influence on the marketplace. If I were a producer, I wouldn’t like it either.

The U.S. documentary film Mondovino recently caused quite a stir in France.

The U.S. documentary film Mondovino recently caused quite a stir in France. No question about it. I think I could argue that case and get a unanimous opinion in any court of law in the world. First of all, just look at the prices that they’re getting for their wines. Take every château that was selling wine back in 1978 and see how well they’re selling now, how well the owners are living now. Then look at how many wines that weren’t even reviewed 25 years ago are now being reviewed positively by me and other critics. Winemakers who are trying to do something special now know that there are critics who will recognize what they’re doing. Quality wine is expensive to make and involves taking risks, so if a wine does get good reviews, that exposure ensures a certain consumer interest that will support their courage, their financial commitment and their sacrifice in trying to make something special.

The result is a proliferation of quality wines.

To put it in another context, visit a top wine shop in the USA today. At least 100 to 150 Bordeaux châteaux are represented and sold to consumers. A quarter of a century ago, there were no more than 20 to 25 estates.

This article originally appeared in FRANCE Magazine - www.francemagazine.org